In the Orthodox tradition the Christians always celebrate Constantine and his mother Helena together on the 21 May. For those who are not that familiarized with them, it sounds as if they were a married couple, an emperor and his empress: Saints Constantine and Helena, that are on the same rank as the Apostles.

Although incorrect at so many levels, for example Helena was never an empress, although she was married to Constantius Chlorus, but before he became emperor in the Tetrarchy, still this associations might reflect the strong relationship that existed between Constantine and his mother.

If Constantine is revered by the Church for his role in ending the persecutions and for promoting Christian faith and Church unity, Helena is remembered for discovering the Holy Cross and for the building of Churches in the Holy Land during her pilgrimage there.

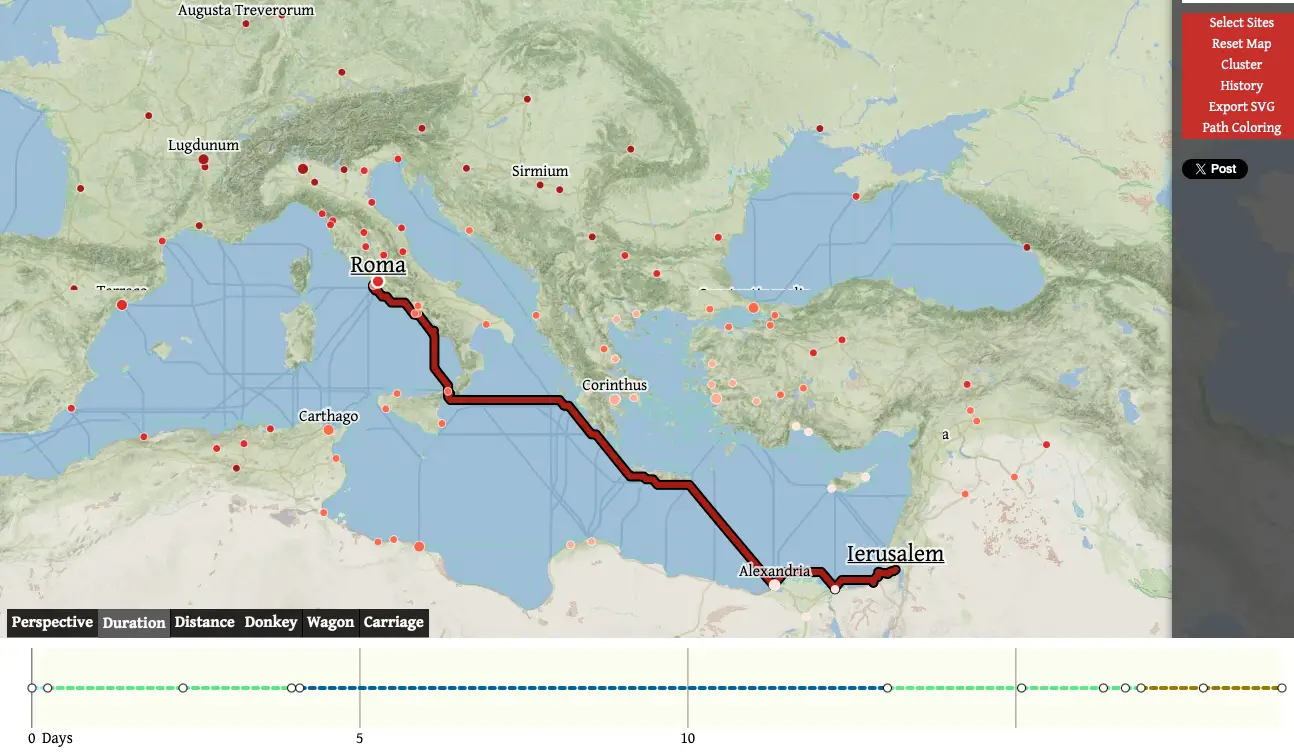

However, it came as a total surprise to me to find out that the pilgrimage to the Holy Lands Helena undertook at a very advanced age, when she was almost 80. And it wasn’t by airplane and busses with air conditioning, but by man powered ships, carriages and horses, spending weeks (at least 20 days from Rome to Jerusalem although this is totally unrealistic given Helena’s advanced age) on the road just to get there.

So, why did she go on this pilgrimage then and not earlier?

One explanation might be that Constantine only became Emperor in the East in 324 AD when he defeated Licinius at the Battles of Chrysopolis and Hellespont. However, the relationship with Licinius, although tense most of the time, still had its moments of relaxation as the joint proclamation in 317 AD of Licinius’ and Constantine’s sons as Caesares proves it.

Another explanation might be linked to the famous year of 326 AD when both Crispus, Constantine’s oldest son, and Fausta, Constantine’s wife, died.

Constantine and Trier

Everyone knows that before it was called Istanbul, the city was called Constantinople for about a millennium, after the great Roman Emperor Constantine the Great who found it, later a saint in the Orthodox (Byzantine) Church.

But few know that there is another city that bare the marks of the presence of the great Emperor that made Christianity a legal religion, namely Trier in Germany.

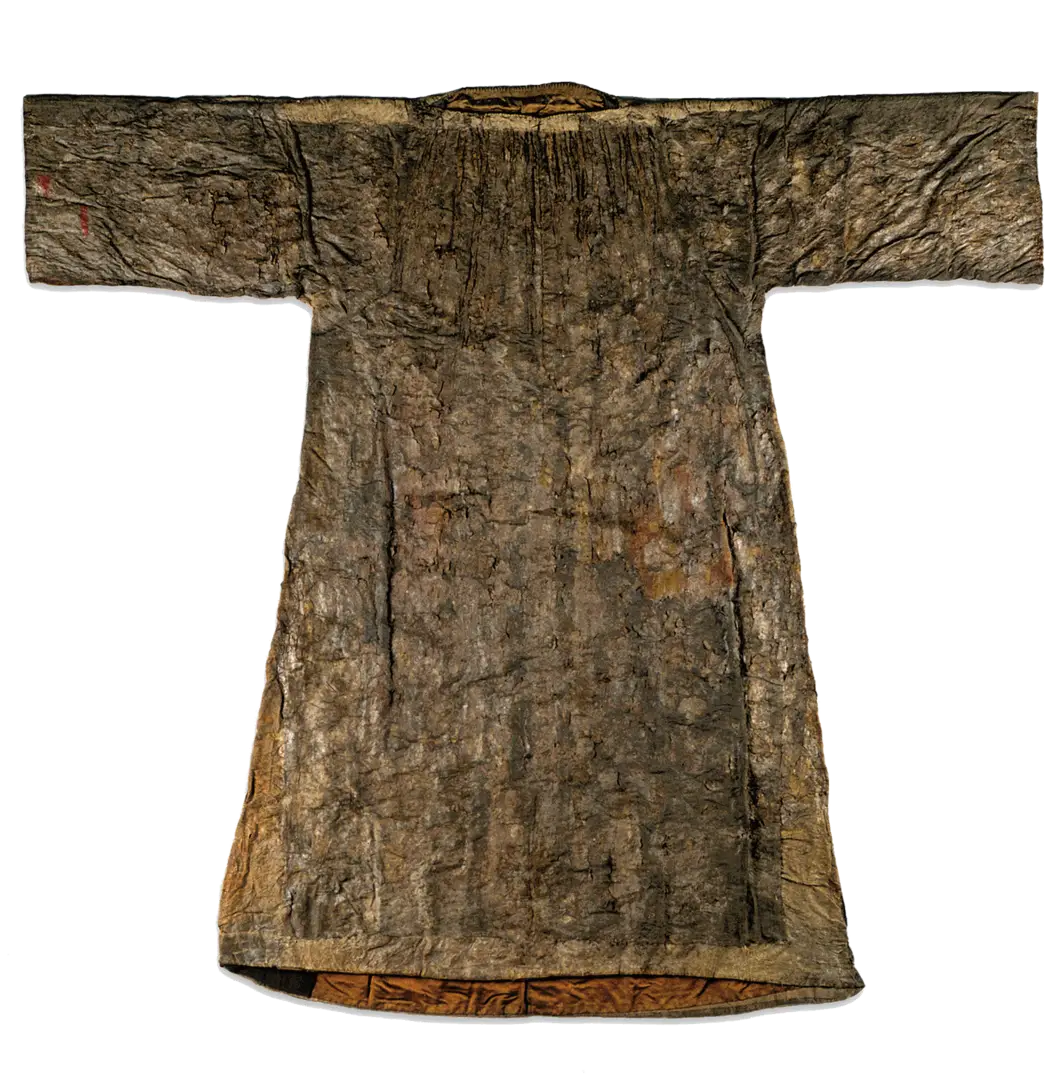

In Trier one can still see the Basilica (Aula Palatina), Constantine’s throne room which has been used as a church, or the Cathedral, also a construction from Constantine’s period whom he built on the place of his mother’s, St. Helena, palace. Famous Christian relics such as Christ’s tunic and nails from His Cross can be revered here, relics brought over from the Holy Land by St. Helena who, according to the Tradition, has also discovered Christ’s Cross. As Constantinople, Trier too speaks volumes about Constantine’s faith and presence.

Before moving to Constantinople after 330 AD, Constantine’s main capital was not so much Rome, which though not entirely abandoned, it has been nevertheless neglected by the Roman Emperors. Nor was it Nicomedia where Constantine spent a large part of his youth as a “guest” to Diocletian’s court. For Constantine, as it was for his father Constantius Chlorus and for Constantine’s eldest son, the Caesar Crispus, Trier was the capital city.

It is in Trier that Constantin calls the Christian writer Lactantius to assist with the education of his son Crispus and it is in Trier, among other places, that Constantine issues coins with Crispus as Caesar.

Crispus and Fausta

However, when in 337 AD Constantine the Great dies, Crispus is not among his successors, but one finds only Constantine II (Flavius Claudius Constantinus; 316 – 340), Constantius II (Flavius Julius Constantius, 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) and Constans (Flavius Julius Constans c. 323 – 350), whom the army declare co-emperors. So, what happened to Constantine’s son, the one who played a key role in the campaign from 323-324 AD against his brother-in-law, Licinius, and who was already a seasoned soldier and a Caesar, while his father was Augustus?

Crispus’ story is a very strange one and it is bound with that of his stepmother Flavia Maxima Fausta Augusta, although not everyone agrees with that.

In brief, the historical sources tell us that both Fausta and Crispus were put to death in the same year 326 AD at Constantine’s orders, because of an alleged affair they entertained most likely in Trier..

How can one believe such a story when by that time Constantine was a champion of Christianity? In 325 AD he had just attended the sessions of the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea, which he convened. Crispus already had a child and his wife seems to have been expecting a second one. Furthermore, Constantine and Fausta were most of the time in the East whereas Crispus was living in the West in Trier. What is even stranger is that the Orthodox Church holds Constantine as a Saint till today.

Constantine and the Family Relations

One may argue that killing members of his family was not something new to Constantine since he also killed his father-in-law, the former Augustus Maximian (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus, c. 250 – c. July 310), and his brothers-in-law, first Maximian’s son, Maxentius (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, c. 283 – 28 October 312) at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on 28 October 312, and then Licinius (Valerius Licinianus Licinius, c. 265 – 325) who was married to Constantine’s half-sister Flavia Julia Constantia.

But this is different. Crispus was no political threat for Constantine, nor was there a fallout between the two that we know about, but rather he seems to represent Constantine’s dynastic future.

As for Fausta, she is no power broker, since she is no Agrippina the Younger.

Furthermore, the Roman Empire of the Constantinian period is far from the one of Claudius or Nero or even of Domitian. The only power struggle the Empire knew for about a century was that between rival emperors and Constantine now ruled alone, uncontested.

So, how come that the one that will enter the history books as the first Christian Emperor, will have attached to his name not one, but two infamous murders that would have never been left uncondemned by an ever more intolerant Christian Church?

Some Possible Explanations

hings are unclear as to what really happened and why. However, there are some theories that might clarify this strange episode from Constantine’s reign.

One theory plays on the trope of the stepmother, so well-known in the history of the Roman Empire. Crispus was not Constantine’s son with Fausta, with whom Constantine had 5 more children: Constantine, Constantius and Constans plus two girls, Constantina and Helena. But he was the fruit of a previous relationship Constantin had with Minervina, a concubine or Constantine’s first wife who seems to have died. Again, things are not clear as to the nature of Constantine’s relationship to Minervina, but it seems to mirror Constantius Chlorus relationship with Helena, his first wife and Constantine’s mother, whom, for political reasons, he divorced to marry Flavia Maximiana Theodora, Maximinian’s daughter.

In this context, to protect her own sons’ interests, Flavia brought against Crispus accusations of seduction and rape and in consequence Constantine executes his son in Pola (today Croatia) by poisoning, a very uncommon method of execution.

Once the truth is found out, Constantine executes his wife too, also in a very strange way, by closing her in an overheated bath. What is even more interesting is that behind Fausta’s death seems to stay none other than Saint Helena, who instigates Constantine against her and opened his eyes as to the truth about to Fausta’s allegations against Crispus.

However, there are other theories that try to explain these two apparently related deaths. For example, David Woods in an article called “On the Death of Empress Fausta,” contends, not without arguments, that Fausta’s death was in fact an accident as he believes that there seems to be an abortion that went south. Yet again, the one that might have assisted Fausta with the abortion in the hot bath might have been Helena herself. As a trustworthy adviser to the emperor and given the fact that the child might have been Crispus’s child, the whole affair needed to be handled with utmost discretion, hence Helena manages the abortion.

Helena and the Pilgrimage to Palestine

This theory might justify why Helena embarked the very same year 326 AD in September, at an age of almost 80 years, on an exhaustive pilgrimage of 2 years to the Holy Places. Of course, the simple loss of a nephew and a daughter-in-law in one year would have been enough reasons to start a soul-searching journey, but there is more than that when it comes to Helena’s pilgrimage. In any case, this is not a political stunt meant to boost Constantine’s image among Christians. He didn’t need it. He was sole emperor, he promoted Christianity, his war against Licinius was promoted as an action to stop persecutions against Christians, and he has just organized the largest council of bishops in Nicaea to bring peace among the various Christian groups.

So, there are no other indications that might point to something else that this exhausting pilgrimage Helena undertook is nothing else but a purely religious act of penitence.

One should not forget that during her pilgrimage, besides doing religiously focused archeological investigations, Helena also builds or endows churches such as the Basilica of the Nativity, the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, and Church of the Holy Sepulcher. These acts performed by a Christian as Helena, should be interpreted as Christian practices of expiation and atonement. Furthermore, the search for expiation does not have to be for the person that does the pilgrimage or makes the donations, as it can be done on behalf of someone else. And it is well known that the pilgrimage to Palestine and all the donations to the churches were financed with generosity by Constantine himself. In 329 AD at almost 80 years, Helena dies. Today, parts of her relics (the skull) are found in Trier.

If between Crispus’ poisoning and Flavia’s very strange death in the hot bath in the fatal year of 326 AD is a direct relationship, it is hard to say with 100% certitude. However, the fact that both suffered damnatio memoriae seem to point towards something more than just a strange coincidence or a bad press from a pagan historian.